Agustín Carstens, the General Manager of the Bank of International Settlements, has given a lecture entitled “Money in the digital age: what role for central banks?” in which he argued that “authorities must be prepared to act against the invasive spread of cryptocurrencies to protect consumers and investors.” The lecture was given in Frankfurt at an event organised by a research centre called Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe.

Readers of the news will be aware of financial leaders being sceptical of Bitcoin. Some have called it a fraud, some have called it a bubble. Carstens went further, saying that Bitcoin is both a bubble and a Ponzi scheme, and even added “environmental disaster” for good measure.

The basic gist of the speech was that technology is good, but new currencies are bad because they are not really currencies and they undermine the banks, which are “stewards of public trust”.

In this article I will briefly describe his speech and the logic behind his conclusion.

What is money?

Carstens began by giving an introduction to the concept of money. As the ‘double coincidence of wants’ is unlikely in a society larger than a small village, barter is not a workable option in society. This is why we use tokens that represent value, a kind of IOU that we all trust. Many things have been used to this end:

But history shows us that the only transfer of value that works is currency “supported by some form of institutional arrangement”.

Private money

Carstens provides examples of financial disasters that happened due to the lack of a central governing body. The ‘free banking era’ in the United States in the 19th century was a time when banks were free to issue currency at will, without oversight, which led to notes that did not function as mediums of exchange, and general financial instability. It was this that led to the eventual creation of the Federal Reserve.

In Mexico, a similar situation existed at the beginning of the 20th century, the upshot of which was the Bank of Mexico being enshrined in the national constitution as the sole issuer of currency.

Using these examples, Carstens implies that cryptocurrency is a kind of private money, and argues that a central bank is essential to financial stability.

Why we need central banks

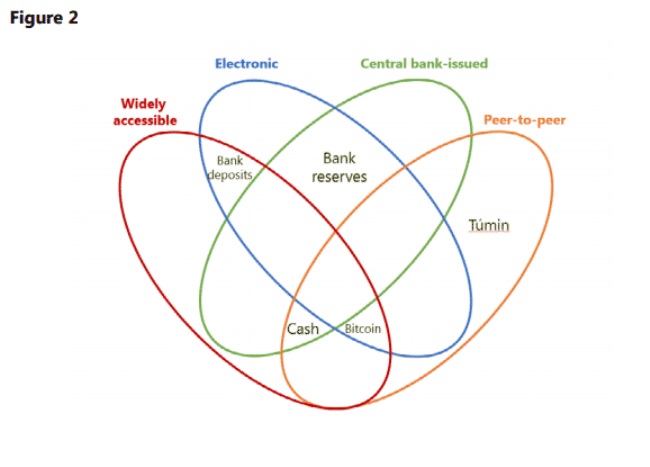

To Carstens, the vital commodity that central banks supply is trust, which is indeed the one thing fundamental to the operation of any currency. He argues that money comes in many forms, and can be transferred in all manner of different ways, it can be supported by commodities like gold or not, but at the end of the day it must have the backing of an institution: “The tried, trusted and resilient modern way to provide confidence in public money is the independent central bank.”

He notes that the technology behind cryptocurrency is not threatening in itself: “Digitalisation is nothing new: financial services and most forms of money have been largely digital for many years. Much of the ongoing transformation is just adding a mobile version for many services, which means that the device becomes a virtual extension of the institution.”

The problems of cryptocurrency

In the speech, Carstens organises his criticism of cryptocurrency into three sections:

#1 – Debasement

He compares the forking of blockchains to the minting of private currency, as described above, and the practice of Kipper und Wipperzeit – the physical clipping of coins as practiced in the pre-unification German states during the Thirty Years War (1618–48), which was “associated with one of the most severe economic crises ever recorded”. He notes that this crisis was, incidentally, solved by the actions of public deposit banks (“precursors of modern central banks”).

His argument is that forks dilute the value of the original currency. He mentions the 19 forks of Bitcoin in 2017 as an example.

#2 – Trust

With cryptocurrency, Carstens argues, no individual or institution is liable, and “concentration of their ownership, could make them even less trustworthy.” He accuses them of piggybacking “on the same institutional infrastructure that serves the overall financial system and on the trust that it provides.”

#3 – Inefficiency

Carsten says that volatility makes cryptocurrency a poor means of payment and “a crazy way to store value”, and the amount of electricity needed to run a blockchain means that “DLT-based systems are very expensive to run and slower and much less efficient to operate than conventional payment and settlement systems.”

Thus, the only real value that Carstens can see is the capacity for use in illegality: “There is a strong case for policy intervention.”

Conclusion

“While not fully immune from the temptation to cheat, central banks as an institution are hard to beat in terms of safeguarding society’s economic and political interest in a stable currency.”

Carstens argues that it is imperative that central banks act pre-preemptively “to safeguard payment systems”, because although the cryptocurrency-based economy is at the present time relatively small, it could grow to “become a threat to financial stability.”

He considers it “alarming” that some banks offer Bitcoin ATMs, because in his opinion Bitcoin is masquerading as a currency while relying “on the oxygen provided by the connection to standard means of payments and trading apps that link users to conventional bank accounts.”

Questionable history

The BIS is often called the ‘central bank of central banks’. It has quite a history – established in 1930 by the victorious nations of the First World War, its original purpose was to facilitate German reperations as stipulated in the Treaty of Versaille. This purpose didn’t last for long, because Germany by that time was in no state to continue paying.

During the Second World War, the bank was supposed to be neutral. However prominent Nazis and German industrialists sat on its managing board and it was a great help to Nazi Germany, processing the state’s plundered loot. As a result of this the bank was marked for liquidiation by the unimpressed Allied powers after the war. However this didn’t happen, and the bank took on the new role of maintaining international currency convertibility.

Since the 1970s, its mandate has been to maintain international financial stability. It provides banking services to institutions such as the European Central Bank and Federal Reserve from its base in Basel.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)